VISUAL PARK

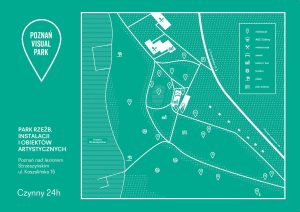

A park of sculptures and art objects, unique in Poland, is being created in the public space at Lake Strzeszyńskie in Poznań. While such venues are common in Western Europe, they are still rare in Poland. The few collections of sculptures in public spaces are most often scattered in the urbanspace (e.g. the exquisite collection in Elbląg), which significantly hampers the sightseeing. If the Visual Park projects develops as planned,Poznań stands a chance of becoming the leading centre promoting the contemporary art of spatial forms. Moreover, the premises at Lake Strzeszyńskie (patterned after centres such as Luisiana near Copenhagen and Kroller-Muller in the Netherlands) will become attractive for tourists, a venue of free and natural contact with art and education for the city residents.

VISUAL PARK is a space arranged to provoke a conscious, cautious, cognitive, and critical observation of reality. The objects installed are moreover elements of the education program, which forms the project’s integral part.

The educational aspect of the VISUAL PARK – THE ART OF SEEING facilitates an unconventional and innovative combination of seemingly distant areas, such as various disciplines of the visual arts, contemporary art and its conscious and critical reception, biology and ecology (the VISUAL PARK includes an educational Eco-Meadow).

All the objects within the Visual Park feature plaques which contain, apart from the author’s name and the title, also a series of questions directing the viewers towards interpretation pathsand provoking their own individual readings of the possible signification of the works. The information on the plaques is supplemented in the free Visual Park Guide (to be picked at the ABC Gallery), where the viewers will find the map of the objects, detailed descriptions of the sculptures and information about their authors.

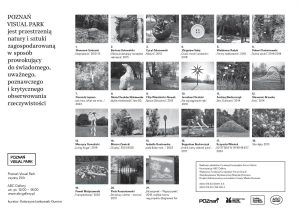

1. FILIP WIERZBICKI – NOWAK, SPACE DELUSIONS, 2012

2. CYRYL ZAKRZEWSKI, MALUM, 2013

3. SŁAWOMIR SOBCZAK, TENSION, 2012 – 13

4. ANDRZEJ BEDNARCZYK, GULLIVER’S DREAM, 2014

5. SŁAWOMIR BRZOSKA, AXIS, 2014

6. BARTOSZ KOKOSIŃSKI, A PAINTING DEVOURING RECREATION TOOLS, 2015

7. WALDEMAR RUDYK, WATERFRONT FORMS, 2015

8. PIOTR KORZENIOWSKI, FLEETING STRUCTURES – REED, 2016

9. MAURYCY GOMULICKI, LIVING SUGAR, 2016

10. JAROSŁAW FLICIŃSKI, AT YOUR FINGERTIPS, 2016

11. BOGUSŁAW BACHORCZYK, THE RABBIT WHICH SAW THE FUTURE, 2017

12. ZBIGNIEW SAŁAJ, A BUTTON OF THE THEORY OF VISION, 2018

13. ROBERT KUŚMIROWSKI, ART TOWER GRADUATION, 2014-18

14. STRZESZYNEK-WYPOCZYNEK, 2019

15. PAWEŁ MATYSZEWSKI “TRANSPLANTACJE”, 2020

16. MARCIN ZAWICKI, MUSHROOMS, 2022

17. IZABELLA GUSTOWSKA, SIAŁA BABA MAK, 2023

18. DOMINIK LEJMAN, WE MISS, WHAT WE MISS, 2023

19. KRZYSZTOF MANIAK, 52°27’36.6″N 16°49’48.6″E , 2024

20. SHE – BEAR

21. ECO MEADOW

POZNAŃ VISUAL PARK GUIDE

People say that “looking is not seeing”. This increasingly applies to each and every one of us. Have we become less perceptive? Less attentive? Less reflective? Why so?

Every day we are bombarded with a barrage of visual stimuli: advertisements, television shots, the Internet, large screens; thousands of images flicker before our eyes as if in a crazy kaleidoscope. Add to this the constant hustle and bustle, the stress and the rush… Unable to take in all with which the visual environment burdens us,we instinctively “scan” reality, receive itfragmentarily and superficially. We often view the world solely via the computer screen. What is it that we lose?

The VISUAL PARK is an invitation to a game of seeing. Zbigniew Herbert observed that “staring” is one of the principal elements of his writing. All of us get to know the world as we move forward and we ourselves develop in the process: seeing – cognition – comprehension – creation. It all starts with seeing. We therefore encourage you to stop to stare. There is plenty to stare at.

The VISUAL PARK contains works by contemporary artists and offers an insight into their perception of the world and the things they want to share with us. You can enter the ABC Gallery to watch the current show and to pick up a free VISUAL PARK GUIDE, which will help you in your tour around the park.You can also attend the workshops we advertise in the bookmarks workshops residencies and what’s on.

Seeing may be a wonderful adventure.

Enjoy

SŁAWOMIR SOBCZAK, “TENSION”, 2012/13

- what is it that stones are not silent about?

- silence – can it be heard?

- what has movement to do with music?

We sometimes use expressions like “mute as a stone” or “stone-dead”. However, a stone is a very intriguing structure: even the tiniest of them has its form, shape and weight. It can be hard and soft, rough or smooth, warm or cold; each has its own colour. Suffice it to pick up a pebble from the ground: have a closer look at it and feel it in the hand. Then the stone, with its unique shape, temperature, colour, and smell will start telling its entire history: how and when did it originate, what processes formed it, did it lie in the forest, overgrown with moss, rolled for centuries by speedy stream watersor, on the contrary, gently stroked by the waves of a lake; perhaps it lay somewhere deep in the ground, or formed a part of some building.

A genuine and complete silence – are we capable of experiencing it? It turns out that even locked in a sound-proof room, cut off from all external auditory stimuli, we begin to hear our heartbeat, our breath and the pounding in the ears. Silence does not exist: the entire world is abuzz – wind, water, leaves, our organisms. Nature incessantly hums, booms, vibrates, rustles, hisses, clucks, and produces sound – delicately. It is often inaudible due to the noise of civilisation. Even here, inStrzeszynek, rarely do we notice the chirping of birds, the rustle of the foliage, and the ginger movements of the waves of the lake.

The stone from Sławek Sobczak’s work is not mute. It tells its own story with its shape, colour and weight. It tautens a string, which allows us to hear the music of nature:alight wind has blown. A stronger gust now. Someone has moved the stone. A sparrow has perched on the string. Raindrops have plucked it. It is freezing outside;the string has become stiffer and the sound it generates is different than on a hot day. Can we hear all that? All we need is stand still for a while, stop taking, turn off the phone, and take a deep breath…

BARTOSZ KOKOSIŃSKI, “A PAINTING DEVOURING RECREATION TOOLS”, 2015

- why is this a painting?

- what are tools for?

- recreation without tools – is it possible?

- when does recreation become slavery?

A Painting Devouring Recreation Toolsis part of a series of paintings by B. Kokosiński inspired by classical painting themes such as religious, battle and genre scenes, still-lifes, and landscapes. The work located outside the gallery merges with the landscape, which is a source of both its inspiration and material. To compose it, the artist made use of the objects from the children’s playground, water bicycles, boats, swimming suits, fishing rods, balls, and elements from the park – parts of benches, fence and pier, etc., associated with the past, like that represented in postcards from the 1970s and 80s.

Places like Strzeszynek in Poznań have been changing rapidlyrecently. However, although revitalised, the continue to bear traces of their past, a narrative of the history of the places themselves as well as the customs, needs and interests of the people who have used them. The old is incorporated and digested by the new and by nature, slowly becoming their part and parcel, element and trace. In a similar manner, A Painting Devouring Recreation Toolsgathers and incorporates the unwanted and unused elements of landscape. The furnishings making up the composition are original, come from the 1970s and 80s, bearing witness to the self-restraint, sweat, blood, will to exercise, and hope for relaxation and health of thousands of people. They are likewise a mute question about their indispensability in pursuit of relaxation and health.Why do we need more and more specialised equipment simply to relax? Do we really need it?Has not recreation equipment become a fetishand tool of pressure of fads, trends, cult of the body, youth, permanent wellness and fitness? Has not recreation itself transformed from relaxation and pleasure into another task to be performed?

CYRYL ZAKRZEWSKI, “MALUM”, 2013

- what does malum mean (Latin)?

- what does a sphere symbolise?

- where do we draw the line between harmony and chaos?

The object has the shape of a sphere made of tree bark. In the European culture the sphere is seen as the acme of perfection, bringing to mind associations with infinity, symbolic of the earth and the universe, peace, fullness, cohesion, and harmony. The sculpture material is also rich in symbolic meaning. Wood:in all old myths, from the far North to the Mediterranean See, it is a symbol of life, vitality, endurance, wisdom, and nature. The Scandinavians believed that the entire world rests on branches of an evergreen ash tree, in Greek mythology there was a tree that bore golden apples, Buddha was enlightened under the tree of wisdom, and the biblical Adam and Eveate their apple under the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

At one point the sphere opens up like a fruit. A pile of old, dilapidated furniture sticks out of it. The material the furniture was made of is also wood; this time, however, it is dead, processed, a product of our civilisation. A tree transformed into wood loses all of its magic properties: it ceases to be a symbol of life and power and will not be reborn in the spring. Useful for a brief moment, it quickly becomes waste, a sign of degradation, passage of time, chaos, and death.

The author clearly juxtaposes the wisdom, vitality, permanence, andperfection of nature with the transient andmutable civilisation. Malum has two meanings in Latin: “evil, misery, mishap”, but also “apple”, a fruit from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, the one eaten by Adam and Eve in Paradise. The apple of paradise was meant to teach us how to distinguish between good and evil. Can we? Have we learned to harmoniously link the civilisation we have ourselves created with nature, which is indispensable for us?

ZBIGNIEW SAŁAJ, A BUTTON OF THE TEORY OF VISION, 2018

As the title of Zbigniew Sałaj’s work clearly indicates, his monumental white button enters into a dialogue with Władysław Strzemiński’s canonical text, calling its content into question. In his artistic practice, Sałaj very often refers to simple objects of everyday use: he frees them of their original roles, changes the materials from which they are traditionally made, tampers with their scale, and distorts their functions.

The objects with which we surround ourselves play a specific role in our lives, and when they no longer perform this role and become redundant, they finish their lives in the dustbin. The world of objects freed from their utilitarian functions opens up a vast field of action, in which children and artists often and willingly engage. The former experimentally transform an object into a kind of toy, the latter explore its more complex aspects. By the artist’s own admission: “Old buttons, wooden thread bobbins, buckles, match boxes, and packaging are the objects that since childhood have triggered my imagination the strongest, driving creative reflexes, which in effect led to the construction of toy objects with deformed function and visuality.”

The title of A Button to the Vision Theory, installed in Poznań Visual Park, implies a game between culture-specific vision and what evades rules and principles and provides an ironic commentary to our conviction of the value and the unquestionability of knowledge, as well as attempts to rationalize and theorize the complex mechanisms of human memory and perception of reality.

WALDEMAR RUDYK, “WATERFRONT FORMS”, 2015

- what is abstraction?

- what is an archetype?

- why is it associated with a lake?

The artistic work of Waldemar Rudyk refers to archetypical concepts. An archetype (from Greek arche – beginning, typos – type) is a prototype of a person, an event, an object, or a motif; it is a picture instilled in the collective memory and created over time by people from a given cultural area.

It is due to this collective memory that we associate a horizontal line with the horizon, crossing lines with a grate, with a closure and a limitation; the colour red with fire, the colour brown with soil, a full circle with the Sun, and a section of this circle with the Moon.

The forms created by Waldemar Rudyk do not reflect objects found in nature because they are abstract and thus nonrepresentational. By observing individual objects, the author has abstracted a form, which is not a copy of those objects, but reflects their common characteristics. It is due to the archetypes ingrained in our collective memory that whenever we see a longitudinal form that is thicker in the middle and narrowing towards the ends, we associate it with the shape of a fish or a boat, even if the form is minimalistic and devoid of details.

ROBERT KUŚMIROWSKI, ART TOWER GRADUATION, 2014-18

The Graduation Tower of Art by R. Kuśmirowski, one of the most important and valued works of this artist, is a monumental sculptural installation created in 2014. Its form, referring to salt graduation towers, or thorn houses, installed in health resorts, fits perfectly into the context of the leisure and recreational character of the park by Strzeszyńskie Lake. The idea of Kuśmirowski’s Graduation Tower of Art addresses the issues that the artist has been dealing with for years: the palimpsestic nature of individual and collective memory, the question of time and its passage, the falsification and impermanence of ideas and objects (including artefacts), and the extravagance of the material culture. Critics call Robert Kuśmirowski “a brilliant imitator”, “a forger and manipulator of reality”. Most of his art is based on reconstructing and copying old objects, documents, photographs, or rather creating their misleadingly similar imitations. The Graduation Tower of Art combines traditional, visually attractive form with topical and intriguing content which makes you wonder.

The work has been exhibited by many prestigious cultural institutions (e.g. the National Museum in Kraków, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, Lublin Castle Museum in Lublin, by Art-Attack 2015/SPACE in Tbilisi, in University Square in Lviv or in front of the National Forum of Music in Wrocław). Kuśmirowski considers Poznań Visual Park to be an ideal place for the permanent exhibition of his object, which – in line with the artist’s intention – will over the years be slowly absorbed by nature.

“SHE BEAR”

- what is a bear doing at a lake?

- what associations do white bears bring to mind?

- what is the “body language” of the she-bear?

A white She-Bear has stood in Strzeszynek Centre “since time immemorial”. We do not know its author. A former staff Centre member said that shortly after the construction of the Oaza Restaurant finished, a sculpture workshop took place here. There are no documents remaining, no other sculptures except a white bear and small clubs have been preserved… When was it? The Centre was built over 50 years ago, Oaza and the other buildings were built in 1963. They were state-of-the-art back then. However, not renovated for a long time, they fell into disrepair to be finally closed down. Today the sad picture of destruction and decline can only be seen in the photographs hung in the Oaza Restaurant. In 2006 modernisation work began andStrzeszynekwas restored as a beautiful and well cared-for venue of relaxation and recreation.

Our She-Bearis made of concrete, its shape very simple and rather uncouth. It has been preserved as a relic of the past which, although not that distant in temporal terms, is dramatically different from the world we live in now. White bears can be associated with the freezing wilderness of the North, where European civilisation does not reach. During the “iron curtain” era people quipped that Western Europeans sawPoland as a countrywhere polar bears roam the streets like in Siberia. Today, the she-bear from Strzeszynek is a nice and funny keepsake of that time.

FILIP WIERZBICKI-NOWAK, “SPACE DELUSIONS”, 2012

- what is a mirror, a reflection, an illusion?

- reflection – is it reality?

- is the world we see reality or illusion?

- frame – how does it change perception?

Space Delusions is an object which provokes an active observation of the environment. From a distance, in full sunlight the installation, made of mirror steel, is hardly visible and merges with the surrounding greenery. At the same time the mirrors multiply and frame the space. The viewer is surprised by the image “cut out” of the immediate environment: the trees, grass and bushes reflected in the mirrors seem real, and yet are a tad different. The very fact of applying a frame to a section of a known space makes us look up close. The frame rivets attention to the elements of reality we pass by and look at on a daily basis yet fail to notice as they are transparent to us. Human beings, operating every day in a given environment see it through a system of clichés, deeply-ingrained habits and signs. For instance, we know and “see” that trees are green, yet what are their hues? How many shades of green can we encounter in a small clearing? What is the shape of the leaves? We do not notice that. The same fragmentary and blurry vision applies to everything else around us: urban space, interiors and even faces of the people that we meet. What with the excess of visual information and haste imposed by the civilisation ofthe 21st century, such “filtering” seems inevitable yet dramatically impoverishes our perception of reality.

Space Delusions is a perception screen, an optical device for seeing. It teaches attentiveness, concentration andcontemplation. We have come to think that the world we see is the “true reality”. However, our eye acts like a mirror, reflecting an image and transmitting itto the brain via the nervous system. Each of us perceives slightly differently and the reflection (image)generated in our eye becomes our reality. The manner of looking and seeing determines to a great extent our comprehension of reality. Imagine that our eye is built differently, e.g. like a dog’s. Then we would not differentiate between many hues, the shapes would be hazy and we would mainly focus our sight on movement. What would then be our world, culture and the civilisation we would build?

JAROSŁAW FLICIŃSKI, “AT YOUR FINGERTIPS“, 2016

- what does a star symbolise?

- what does panta rei mean?

The Star stands on an elevation next to the place where I swam for the very first time. This was on a sweltering July afternoon in the early 1970s. I entered the lake and, in the presence of a few people who did not bother to pay too much attention to me, swam the backstroke, looking at the sky. I felt an overwhelming pleasure of free movement in the water. I distinctly recall my coming to recognise the significance and possibilities of my new movements, which offered me so much unprecedented freedom.

I came to Poznań for one day in the spring of this year. Quite by chance and to my great surprise, an hour later I found myself in Strzeszynek. I saw the same lake, the same meadows, higher trees and bushes, and a changed restaurant, where one could still vicariously recreate its interior from years before.

A telephone rang in my Portuguese home. An old friend of mine felt obliged to notify me about the death of our mutual acquaintance. I also learned that another friend of ours, by the same name, had passed away somewhat earlier. Hardly had our conversation ended when I had already sketched in my mind a design of a star against the sky. This was two weeks prior to my arrival in Poznań.

I was once commissioned a painting from the Flowers series. Once it was completed, I telephoned to say that it was ready. After a moment of silence, I heard a voice in the receiver saying: “My Mom has died”. I went back to the painting and added stars in the empty squares between the flowers. This marked the beginning of the Flowers and Stars series.

I spent the first days of 2001, full of prophesies for the new century, when nothing pointed to the confluence of events to take place soon afterwards, at the home of my friends near Bordeaux. I was taking pictures of the sun. My paintings had shifted to murals composed exclusively of stripes and large circles. Looking at a photograph of a radiant bright sphere, I decided to change the circle into a pointed star. I first cut out a simple drawing in paper and in the morning blew it up on a white wall and filled up with white, shiny paint. The house has stood there until now and one of its walls still features the White Star, but the house has for many years not been the same; it is completely different.

Everything is in a continuous state of flux. To some extent the changes can be foreseen; sometimes their direction can be changed but they cannot be forestalled completely. Reality simmers like a huge ocean of magma and creates ever new structures. Each day, at any given moment someone goes swimming for the first time in their lives or closes their eyes for the last time. We are somewhere in between.

Jarosław Fliciński

September 2016

ANDRZEJ BEDNARCZYK,”GULLIVER’S DREAM”, 2014

- the Other – who is it?

- the Unknown – does it awaken our curiosity or fear?

- does the world still hold any secrets?

- are we a mystery? For whom?

The history of civilisation and culture proves that eachculture existed and developed in opposition to some “other side”: behind some great water, behind mountain ranges, forests, behind the horizon, in the netherworld, in mythical lands, etc. Collective imagination invariably peopled the “other side” with heroes and monsters. Despite the differences between the individual cultures, the mythical lands have always enkindled human imagination. Living in a global world, we have not got rid of uncharted lands, but they have grown distant enough to stop being a part of our everyday experience, and the heroes and monsters are not so much a figment of our imagination, but characters onmovie, television andcomputer screens.

Gulliver’s Dreamdestroys the barrier of the screen and allows the viewer to peep into the “other side” during a walk along the paths around Lake Strzeszyńskie. At one such path, near the lake beach, there is a telescope which offers a view of the bushes on the other side and …

Andrzej Bednarczyk

SŁAWOMIR BRZOSKA, “AXIS”, 2014

- what does the Latin word axis mean?

- does the world axis exist?

- how did the Slavs imagine it?

- is the universe geometrical?

Sławomir Brzoska equates creative activities with a journey. In the limited space of a gallery, where a string serves for creating geometrical, abstract forms, it is a meditative voyage –

it occurs through reflection about the work of art. However, the real-life wandering through places unpolluted by civilisation, where people have retained the old nomadic lifestyle and where the traveller experiences loneliness and an almost primal union with the nature, is just as important as the spiritual journey. Like the nomadic tribes, the artist also leaves traces during his wayfaring – stones wrapped in wool – which are his personal “travel diaries”. Choosing a particular stone and working with it recaptures one of the earliest human instincts. By making that choice, the artist establishes the Centre, where the chaotic profanum becomes the organised sacrum.

The installation in the Visual Park continues and develops the idea of a symbolic demarcation of the Centre. It refers to the axis mundi (Latin for world axis), a concept which has existed in different cultures from the dawn of time. The world axis (centre of the world, cosmic axis) was believed to be a holy place, a universal reference point, where the time stops and where one has access to both the past and the future. People believed that the process of creating the world began with the axis mundi. Every culture had its own vision of the world axis: the indigenous Australian Aborigines saw it as a holy pillar – a mainstay of the sky, around which the real world was created. The Vikings worshipped a mythical ash tree, while for the Slavs oak trees were holy, but they also assigned magical qualities to mountains, such as Łysa Góra or Ślęża (in Poland).

MAURYCY GOMULICKI “LIVING SUGAR”, 2016

- what can candy be a symbol of?

- what happened to Pinocchio in Toy Land?

Strzeszyn Park was an agreeable surprise for me. It is a facility “resurrected” after a period of decadence under communism, all the time preserving its original function of a sports and recreation centre. As most such venues in our climate zone, Strzeszyn Park changes its character during the year: it is melancholy in autumn and winter, is brought to life in the springtime and reaches its apogee in the summer months. I am interested precisely in this moment of vacation ecstasy, of the semi-holiday which cannot really be called either “summer in the city”, or a complete escape into nature. The area looks like during some festivity: the green beaches are swarming with people and the usually quiet lake resounds with loud calls of the playful swimmers. Colourful stands appear; while their beauty is controversial, they invariably guarantee 5 minutes of sweet abandon. This place is given then to a true excess of waffles eaten by the laughing and shrieking visitors; mega-tonnes of ice-cream melt in the sun onto the warm bodies of adults and kids. There is something ever pleasant in summertime chaos: the vitality of carefree joy and careless play.

With this context at my disposal, I decided to conjure up sweet spirits; my installation is composed of two gigantic pieces of caramel candy, shaped like walking sticks, which resemble traditional candy to be bought during church bazaars; although slightly less popular today, they are still used as Christmas tree decorations. I was intrigued by a large-scale manifestation of a sweet temptation and I decided to implant into this make-believe paradise two guests from Candyland. This delightful area of sinful confectionary excess corresponds with the Paese dei balocchi visited by Pinocchio. The objects are two totems-periscopes which, thanks to their Cyclops’ eyes, become quasi-beings. I do hope that they will be good companions and observers of holiday revelries, especially at a more murky time, when the place will be enveloped in a grey veil. I hope they will remind all that Summer is bound to come back.

Maurycy Gomulicki

B. 1969. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Universitat de Barcelona, Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan, and at the Centro Multimedia del Centro Nacional de las Artes, Mexico. Artist, designer, photographer, collector, and popular culture anthropologist. Hedonist who consistently promotes the Culture of Delights. Author of photographs, videos, animations, and objects. Intense colours, explored in their vital potential and in their sociological and cultural characteristics, are a major element of his oeuvre. He lives and works in Poland and Mexico.

BOGUSŁAW BACHORCZYK, THE RABBIT, WHICH SAW THE FUTURE, 2017

The sculpture has the shape of two cookie cutters. Such cutters, just like the moulds used in the sandbox, are usually associated with childhood, fun and sweets, with home, being carefree and safe. The sculptural composition consists of two dynamic rabbit figures, between which the author created a clearly noticeable tension. The two look as if they were fighting with each other or were about to jump at each other. Oversized (the sculpture is nearly 3.5 m high) and placed in an unusual setting, acquire new, completely different meanings: without losing their innocence of cookie cutters and connotations with toys, “home comforts” and childhood, the rabbits become a metaphor of moulding, forming, oppression and confrontation.

PIOTR KORZENIOWSKI, FLEETING STRUCTURES – REED, 2015

- what does harmony of multiple elements consist of?

- what makes a given set of elements to be perceived as a single whole?

- what is rhythm?

- how does perspective change the perception of form, shape, mass?

The idea behind this composition revolves around the subjects of “population”, “generation” and “community”. At its core, it simply refers to the search for elements that could prove the thesis that similar, recurrent elements of reality – existing in groups and masses – put themselves in order in a fascinating and peculiar manner, creating a kind of an organized structure. What remains shrouded in mystery, at least for me, are the reasons and forces that set this process in motion. I refer to such a structure as “population”, “generation” or even “community”. Not only does it consist of numerous similar elements, but these elements are also united on a superior level by the distinctive binding material of their interrelationship and interdependence. The process which connects, orders and prioritises those elements is, in my opinion, omnipresent and ubiquitous, albeit neither is it conspicuous nor prominent. Thus, I do not relate these processes solely to human community but I seek them obstinately in the realm of flora and fauna, and in all processes, not only the physical ones, governing the animate and inanimate matter. Therefore, to me a forest, grass, reed, a mountain range or a desert form a unique ecosystem of mutual connections and interdependencies, and in this way create some kind of a “community”, “generation” or “population”… The work entitled “Transient structures – Reed” is a type of a simple visual metaphor of the process in which a collection of similar, yet not identical, items forms a population or a community. The binding material of the separate stalks of reed which hierarchises them is an element of a “disparate matter” (where the white colour symbolises light) present in every stalk which in the group of all elements forms a seemingly levitating white geometric solid. Light, or the luminescent solid, is a perfect visual equivalent of strength or of a prioritising and harmonising process. It is in its essence simple yet elusive, ephemeral, non-evident and it, nonetheless, appears meaningful and in some way universal… It makes the separate stalks of reed comprise an “organised community”, a structure governed by the hierarchy and order of the transient but significant idea that bonds it.

Piotr Korzeniowski

STRZESZYNEK WYPOCZYNEK, 2019

PAWEŁ MATYSZEWSKI, TRANSPLANTACJE, 2020

MARCIN ZAWICKI, GRZYBY, 2022

IZABELLA GUSTOWSKA,SIAŁA BABA MAK, 2034

DOMINIK LEJMAN, WE MISS, WHAT WE MISS, 2023

KRZYSZTOF MANIAK, 52°27’36.6″N 16°49’48.6″E, 2024